Just when I think I might know something about women in aviation, or just when we think we’ve heard all the stories about “the greatest generation,” I find out about another group who contributed to the World War II effort. They were not Rosie the Riveters assembling aircraft on production lines nor were they the pilots known as the WASP. By now, most people have heard of the Women Airforce Service Pilots, 1,074 civilian women who, from 1943 to 1944, flew more than 60 million miles ferrying military aircraft, towing targets, and performing other administrative flying duties for the US Army Air Forces. Thirty-eight women lost their lives in the course of their duties to their country, but deceased or living, they received no military benefits.

After being deactivated in December 1944, so that returning male pilots could resume stateside military flight duties, their remarkable story was lost for many years, in fact until 1977 when Congress finally conferred retroactive military status to the WASP. In the 1990s, various WWII 50th anniversary events reintroduced them and finally, in March 2010, the WASP received their ultimate honor with the awarding of Congressional Gold Medal for their service and “revolutionary reform in the Armed Forces” during World War II. Each living WASP or family of a WASP received a bronze medal and National Air and Space Museum became the repository for the single Gold Medal, now displayed at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center. Many books and documentaries now tell the powerful WASP story.

Members of the WASP (Women Airforce Service Pilots) are pictured at Lockbourne Army Air Field in World War II. From left to right are Frances Green, Margaret (Peg) Kirchner, Ann Waldner and Blanche Osborn. The WASP were civilian women pilots who flew in non-combat situations for the U.S. Army Air Forces during the war. The program came to an abrupt end in 1944 because of gender politics.

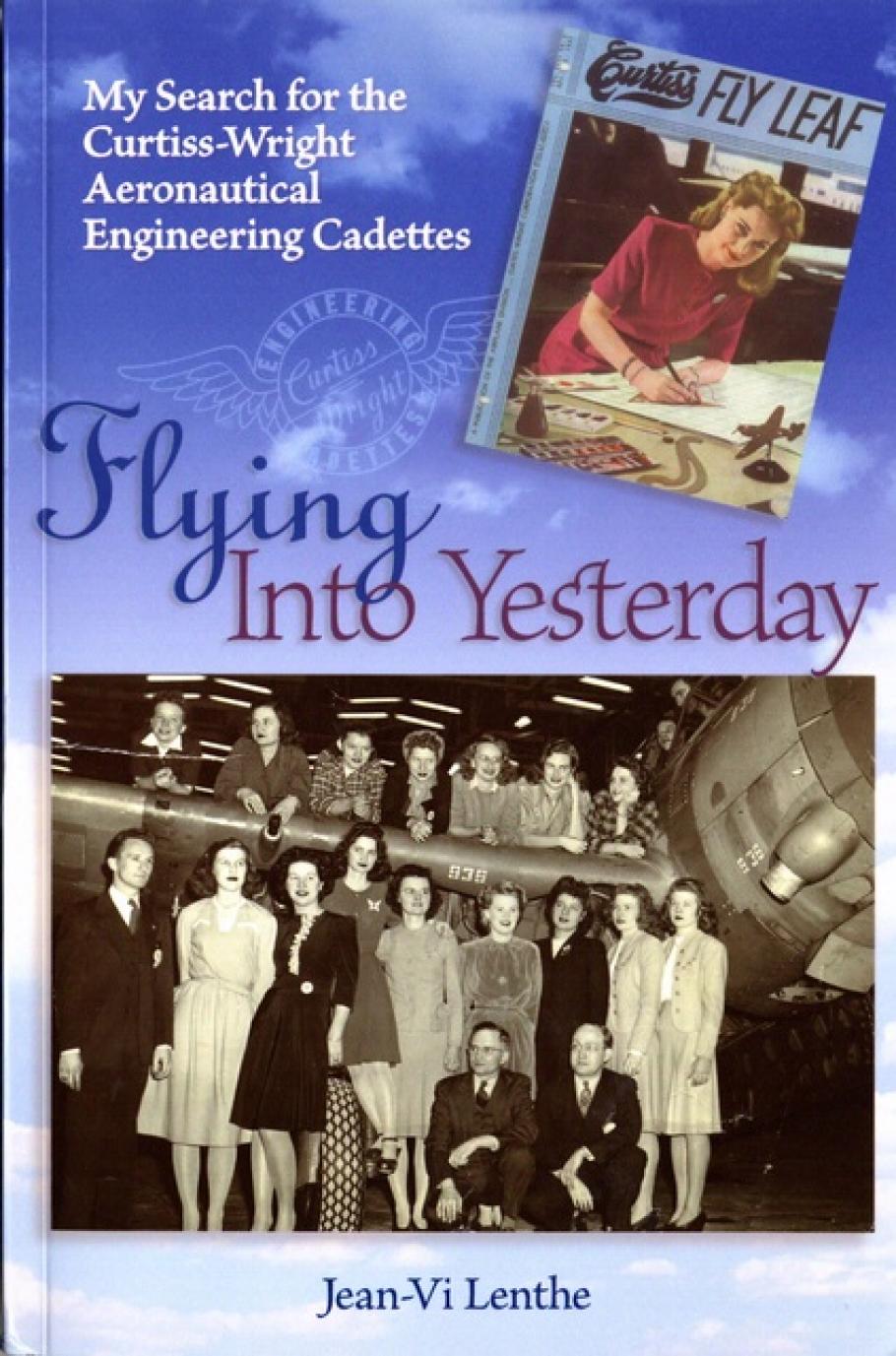

Recently I learned about another group of unheralded women from the World War II era. Last fall Jean-Vi Lenthe e-mailed me about a women’s aeronautical engineering training and employment program sponsored by the Curtiss-Wright Corporation, and although I must have read about it in Deborah Douglas’ American Women in Flight Since 1940, I could not recall the details. Lenthe promptly sent me a copy of her book that tells the story of the intrepid women, including her own mother, known as the Curtiss-Wright Cadettes. Having never spoken in depth about it with her mother before her death, Lenthe became curious and began contacting the remnants of the Curtiss-Wright Corporation, visiting the old Curtiss-Wright plants and repositories of Curtiss-Wright archives (including the National Air and Space Museum unbeknownst to me), and interviewing living Curtiss-Wright Cadettes. How did her mother become involved and what work did she and the rest of co-eds train for and perform? The motivated and tenacious Lenthe was just the person to unravel this puzzle and the result is Flying Into Yesterday My Search for the Curtiss-Wright Aeronautical Engineering Cadettes.

Curtiss-Wright Corporation was a major aircraft manufacturer in World War II producing, among other aircraft, the P-40 Warhawk for the U.S. Army Air Forces and the SB2C Helldiver for the U.S. Navy. The Helldiver saga was a tortuous one with many complex design and production issues and in 1942, Curtiss-Wright was in danger of defaulting on its contract to provide the Navy with a new dive bomber. At the same time, male engineers were being drafted and the company was having trouble keeping up the necessary engineering work to fix the Helldiver and get it into sustained production. So Curtiss-Wright took the highly unusual step of authorizing women to fill in.

Between February 1943 and March 1945, 918 female college students, identified as mathematically advanced, took courses in aerodynamics, engineering, and design at seven universities; 766 Cadettes graduated from the government-sponsored program and began work in five Curtiss-Wright plants. Lenthe focused on her mother, Ricki Cruse Lenthe, who studied at Purdue University and completed the 10-month program condensed down from a two and one half year engineering curriculum that also included technical drawing, airframe structures, and subjects tailored to the work at the plant to which she would be assigned. Her mother reported to the Handbooks Group of the Service Engineering department at the Columbus, Ohio plant where she helped to prepare the Pilot Handbook for the Helldiver. Many Cadettes worked in drafting departments where they incorporated engineering orders into the original working drawings of the Helldiver, accurately modifying the drawings with major or minor changes (which eventually numbered nearly 900) for production use.

It was another Cadette from that plant who years later gave Lenthe the push to research the Cadettes and document their work: Betty Masket, now living in Chevy Chase, Maryland. Masket performed inspections on the production line and once shut it down when she found a clearance issue with the hydraulic line to the dive brakes on the wings. She was concerned the line could be cut and cause an uncontrollable descent of the aircraft. Lenthe called me because she was coming to Washington, DC to see Masket and wanted to bring her to the Udvar-Hazy Center to see our Helldiver undergoing restoration in the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Center. I am sure she was not really surprised when I told her I knew little of the Curtiss-Wright Cadettes, but no doubt she was yet again disappointed. SuperStorm Sandy delayed her trip east from New Mexico but we finally met on January 21.

Visits like this are rewarding aspects of working at the Museum because they have so many layers. Lenthe affirmed her research efforts and the Cadettes identity by linking them to their daily work and accomplishments, in this case Masket with the Helldiver, and Lenthe also made the personal connection to her mother’s work. Masket inspected yet another Helldiver and talked shop with curator Jeremy Kinney and our museum specialists who work on the restoration. Our museum specialists are always delighted to speak with someone with personal knowledge of an aircraft, whether a pilot, mechanic, or female engineer, and they peppered both women with questions. We could not confirm that Masket’s suggested change for the hydraulic line was made, but she thoroughly enjoyed seeing a Helldiver in pieces again and will be back to follow the work. The restorers, Jeremy, and I found out about the Curtiss-Wright Cadettes and we now have another resource for hands-on Helldiver details. I signed up the women for the Museum’s Women in Aviation and Space Family Day on Saturday, March 23. Later in the week, Lenthe and I discussed her growing Cadettes archival and artifact collections and her plans for an exhibit. Our aircraft provided the point of focus for the visit but the true value is in the people, in this case Lenthe, Masket, and the rest of intriguing Curtiss-Wright Aeronautical Engineering Cadettes.

Like the WASP and assembly line workers, the Cadettes were abruptly sent home at the end of World War II. Although they contributed to the production of more than 5,000 Helldivers at the Columbus plant, and more aircraft at other plants, and to propeller and engine programs as well, they did not receive promised help from Curtiss-Wright to finish their engineering degrees after the war. Worse yet, the company lost or threw out records of the program. A few Cadettes went on to become career engineers, some, like Lenthe’s mother, became teachers, and many became homemakers. But whatever they did, they all appreciated their Cadettes experience and the difference it made in their lives. The Chance-Vought Corporation also established a scholarship program with the Daniel Guggenheim School for Aeronautics at New York University that led to the placement of a small number of female engineers in the Chance-Vought Engineering Department. On the whole though, only a handful of women became career engineers for aviation companies; similarly very few women became pilots or stayed in the industry in other capacities. Most everyone regarded women working for the war effort as just that and, when the war ceased, so did their employment. It would be several decades before women permanently entered the workplace in force.

Jean-Vi Lenthe, Betty Masket, and other Curtiss-Wright Cadettes will host a table at the Women in Aviation and Space Family Day at the Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, VA on March 23, 2013, 10:00am-3:00pm Jean-Vi Lenthe will have a book signing from 12:00 - 2:00 pm.