When we think of D-Day, we tend to envision the waves of landing craft approaching the beaches and Landing Craft Tanks (LCTs) with barrage balloons in tow, or maybe waves of C-47s winging away from their bases in Southern England with their paratroopers. These are powerful visuals and while the soldiers and paratroopers really did do the heavy lifting of liberating France, these images overshadow a remarkable and invisible war that is often forgotten. This “Wizard War” was fought with electrons instead of bullets, but it was no less critical in the Allied victory than the expenditure of ordnance.

A radar-equipped B-17G pathfinder of the 91st Bomb Group prepares to take off to bombard the Normandy landing beaches on the morning of June 6, 1944.

While vast arsenals of munitions, men, aircraft, tanks, and planes were assembled in England during the spring of 1944, an equally intensive program was underway to launch an electronic offensive of unparalleled scope and sophistication. Some of these technologies were ready only just in time while others were already in use but new enhancements or capabilities were husbanded in advance of the landings to avoid giving away the Allied advantage.

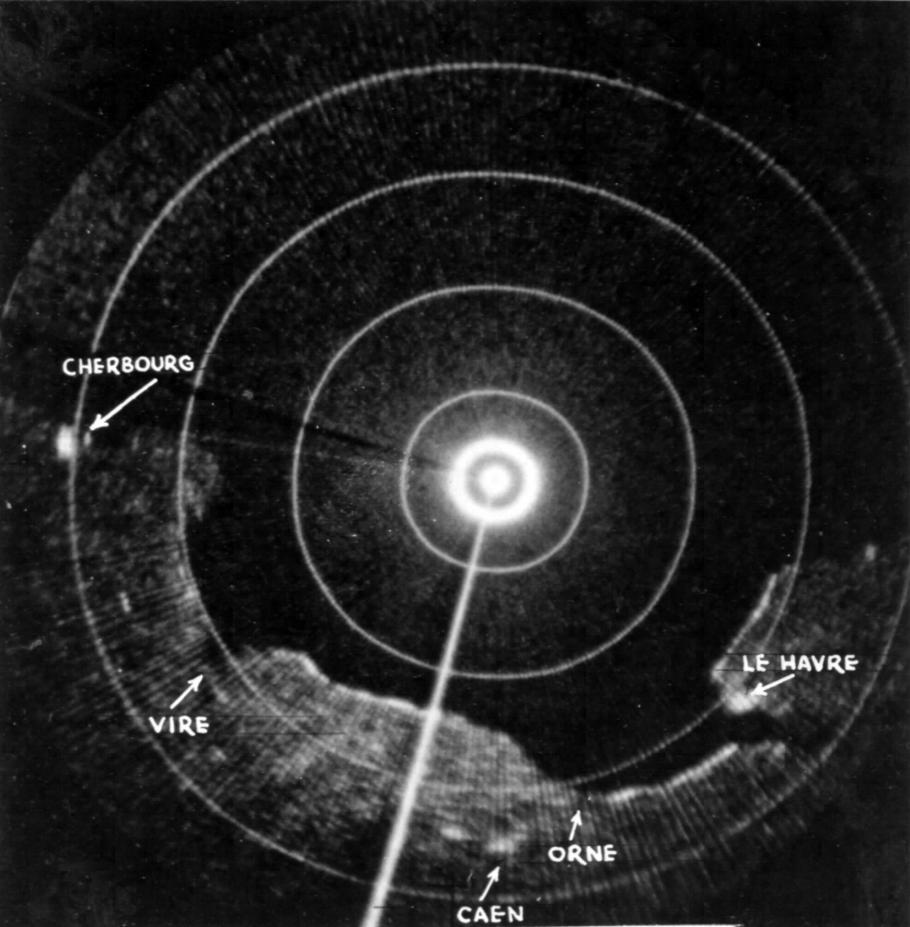

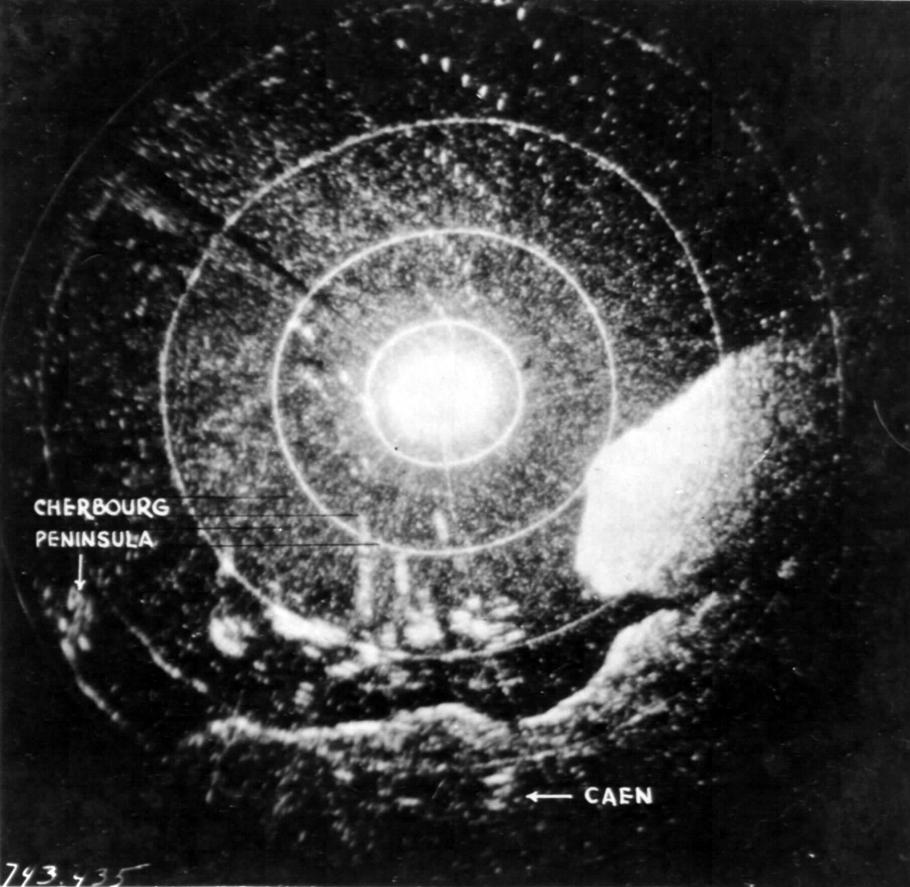

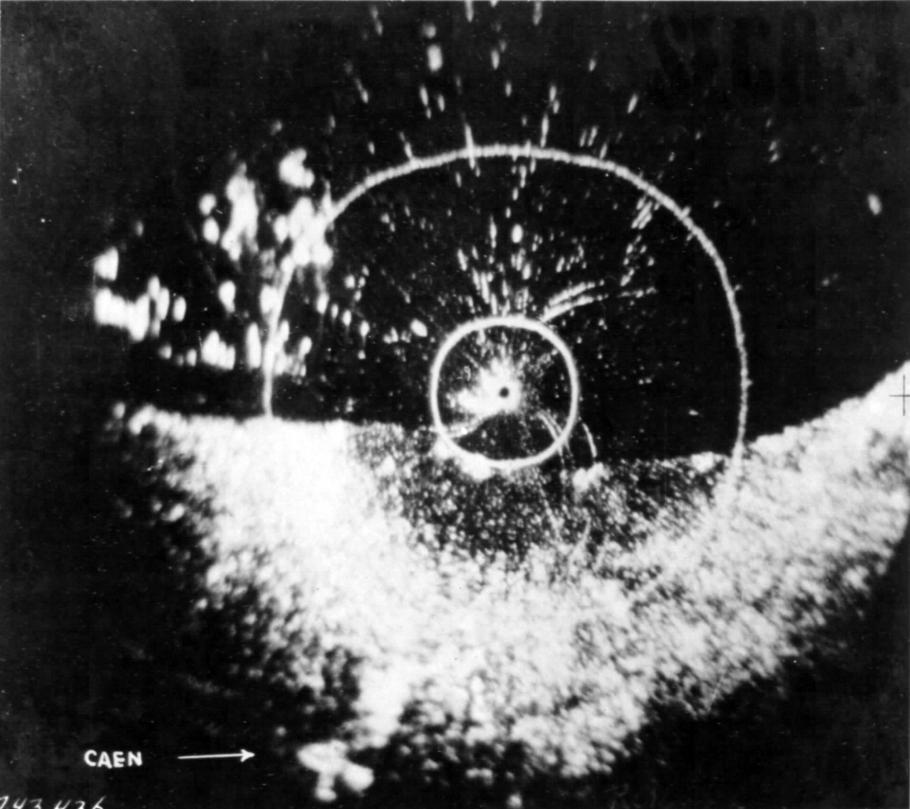

This airborne radar scope image of the Normandy coastline was taken just before the invasion. The area would never look the same again during the war as it would be filled with military shipping.

I’m always a little dismayed to see the exuberance with which some museum visitors regard the German jet and rocket technologies on display at the museum and one often overhears comments to the effect of “if Hitler hadn’t interfered with the Messerschmitt Me 262 production, they could have won the air war.” While it is certainly true that the Germans held a commanding lead in 1944 in jet and rocket production, it is also true that whatever military advantage they offered was vastly overshadowed by many other fields in which the Allies totally overmatched the Germans. This was especially true in regards to the electronic frontier. Here are a few of the remarkable, but overlooked technologies that were essential to the Allied victory in Normandy.

On June 6, the Baie de la Seine was filled with Allied landing craft and shipping. Airborne radar at this time could identify three types of ground features reasonably well – coastlines, ships, and towns.

Radar was used by all sides in World War II and was probably best known for facilitating the British victory in the Battle of Britain. However, radar had come a very long way since the first generation Chain Home radar stations countered the offensive bomber formations of the Blitz. The British development of the cavity magnetron in 1940 made microwave radar possible, giving far greater definition and resistance to jamming than anything the Germans had. By D-Day, the combination of the quartz oscillator and the cavity magnetron had yielded an extensive array of ground-based and aircraft equipment that allowed the offensive resources of the Allies to be applied efficiently and effectively. Without them, the German defenses would have been exceptionally difficult to crack. Though the soldiers on Omaha Beach would never think they had it easy (and as discussed below, they were indeed let down by some of this technology), the reality is that Operation Overlord was about far more than simply having enough men and equipment while tricking the Germans into thinking the landing was occurring elsewhere. At its most basic level, Normandy was a giant navigation problem.

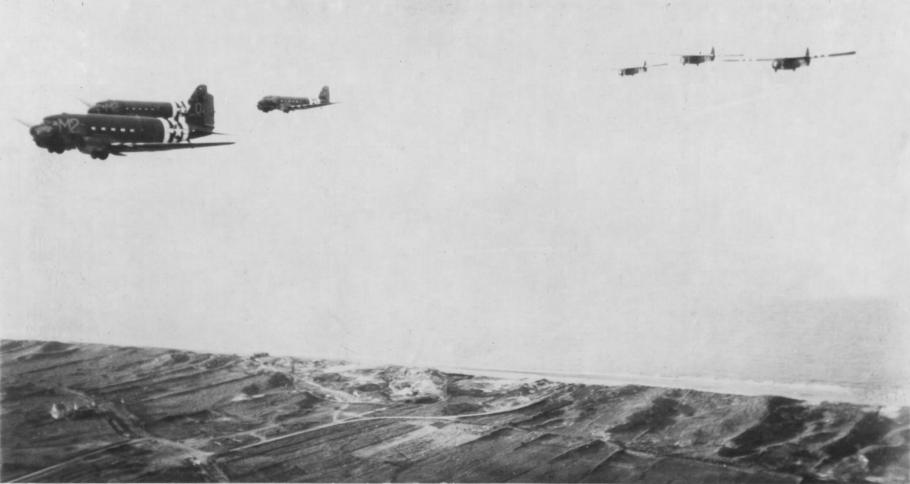

: C-47s of the 9th Air Force Troop Carrier Command tow reinforcements in CG-4 gliders across the Normandy beaches on June 6, 1944. The C-47s used a remarkable radar transponder system called Rebecca-Eureka to find drop zones, but weather delayed the pathfinders who carried the beacons, resulting in many gliders and paratroopers landing in the wrong locations.

Troop transports flying without benefit of radar (they had no room for it) needed to place troops in the right landing zone under cover of darkness. Minesweepers had to clear precise paths through Channel minefields. Bombers had to strike fortifications, bridges and rail yards, even through cloud, and a massive aerial ballet had to occur that simultaneously struck critical targets while not revealing invasion plans. Without the vast electronic armada, the landings would have suffered far greater losses and required an even greater expenditure of lives and resources.

For all-weather navigation, British and American bombers used Gee receivers, like this Type 62A Gee Mark II example, extensively on D-Day and during the Normandy campaign. With modified ground stations it was also useful in relatively accurate “blind bombing” missions.

This list of key electronic system designations used on D-Day was collated by Professor J.W.S. Pringle in his survey of the Telecommunications Research Establishment (Britain’s electronic R&D organization), published as “The Work of TRE in the invasion of Europe (IEEE Proceedings, Vol. 132. Pt. A., No. 6, October 1985). It is not even a complete list of the equipment developed or adapted for the invasion, but it gives a sense of the massive electronic forces arrayed against Germany.

The AN/CPS-1 Microwave Early Warning (MEW) radar deployed in time for D-Day on the south coast of England was a vast improvement over previous ground-based radar networks. Not only did it detect enemy aircraft and Buzz Bombs, but it was extremely effective at guiding Allied combat aircraft to both air and ground targets with a precision that could only have been dreamed of during the Battle of Britain. This example is seen around the time of the Battle of the Bulge in Luxembourg.

Among the remarkable technologies not in the list above was something called Decca. The minesweepers that paved the way for the landing craft at Normandy did not have GPS, but they did have Decca, which had accuracies that were not all that much worse than first generation GPS receivers. Decca was a hyperbolic system started by an American in the late 1930s and developed by the British Decca record company during the first years of World War II. D-Day was its first (and only) operational use in the war. Trials had been conducted in secret in the Irish Sea earlier in the year. You can read more about this fascinating technology here.

The Rebecca-Eureka system, while an excellent way of guiding transport planes to paratrooper drop zones depended on the pathfinder forces with the Eureka beacons to be in the right place at the right time. During the invasion of Normandy, weather delays prevented this. The inability to have the Eureka teams in place is a significant reason why the paratroop landings in the hours before daylight went so wrong.

For everything that went right on D-Day, there were some areas where the Wizard War went very wrong (see the above caption). The worst occurred with the use of radar to bomb the defenses on Omaha Beach. Concerns over having bombs fall short in to the arriving formations of landing craft shortly before they reached the beach resulted in an order to wait 10-30 seconds in bomb release when only using radar. With complete cloud cover on the morning of the invasion, the bomb delay was in full force and nearly all of the 2,944 tons of bombs missed useful targets by a mile or more. The only positive aspect was that some of the minefields behind the beach defenses were hit instead, but overall this one error alone likely contributed many additional hundreds of casualties, if not more, on Omaha and the British landing beaches.

This H2X radar scope image may be from one of the aircraft that missed striking the Normandy landing beach defenses because of orders not to undershoot. The position of the aircraft is near Sword beach, the easternmost of the landing beaches.

These errors aside, the overall electronic armada arrayed for Normandy worked well and most ships and aircraft arrived when and where they were needed. The German electronic defenses were also almost wholly nullified, with radar and communications effectively jammed. The Gee hyperbolic navigation receivers that guided so many ships and aircraft during the invasion were vulnerable to jamming, but extra frequencies had been set aside so that jamming would be easily sidestepped. In the event, German jamming did not appear. D-Day was as much an electronic surprise to the German technicians at their stations behind the beach as it was to those soldiers manning the pillboxes on the beach.

This shelled German Giant Wurzburg radar overlooks a Normandy landing beach, possibly at Point du Hoc. The German radar network was neutralized by a combination of direct attacks, electronic jammers, and the dropping of Chaff. The German air response to the invasion was nearly non-existent as a result.